Tara de Linde – Director, Atelier de Linde Ltd.

As with sculpture, architecture and urban design are as much about what is not there as what is: shadows punctuating light, recesses defining rhythm, translucent materials obscuring definition. In an urban setting, these areas are what I think of as “The Spaces in between”, easily identified on monochrome maps as the random white shapes nestled amongst a network of roads.

The unsuspecting visitor might stumble upon such spaces: a hidden square shaded by a large tree (e.g. the Giant Plane Tree in Bath), a secret passage leading to an historic pub (e.g. The Coach & Horses Passage in Tunbridge Wells leading to the Sussex Arms) or a private/public garden woven between cultural landmarks (e.g. Postman’s Park in London). They delight because they are unexpected, invite deviation and in one way or another connect us with the past.

There is a now a tiered approach to Land Release covering Brownfield (previously developed land) to Greyfield, to Green Belt (Designated land meant to prevent urban sprawl and protect the countryside near cities). Significantly the Grey Belt is not officially defined in the NPFF. It has been left to the Agents (Architects and Planning Consultants) to demonstrate that the land no longer meets the purposes of the Green Belt and has low environmental or visual value. These recent reforms to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) create opportunities for innovative design in both rural and urban settings.

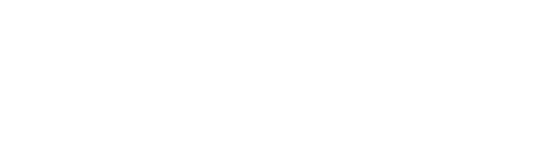

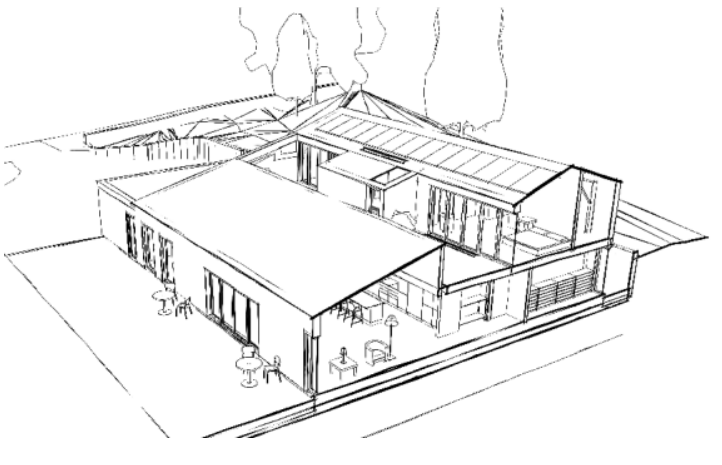

In the Green Belt conversion projects are the perfect canvas for exploring the dichotomy between structure and void. Planning requirements to retain and restore existing fabric allow one to approach a project in a manner not unlike that of a sculptor assessing a slab of stone. We carve away, conscious of the play of light and shade throughout the day, of views through the structure and out towards the surrounding countryside. It is a puzzle, informed by space, void, light, shadow and of course the harnessing and retention of energy. The concealed balconies at the Great Bayhall Barn in Pembury or the clever adaptation of a Sussex Oast House roundel repurposed as a light well for the contemporary kitchen below – both by Atelier de Linde Ltd. – below are fine examples.

Brownfield sites, that conjure up images of disused garages, weedy back lands and abandoned car parks are ideal spaces in which to bring back some poetry into our towns. Such unloved corners can have strong emotive appeal inciting designers and developers to engage in a kind of architectural alchemy, turning forgotten fragments of land into parcels of beauty.

Atelier de Linde Ltd. (architects) were commissioned to redevelop such a corner in the heart of Tunbridge Wells. The site is tucked away down a long driveway, flanked by rundown empty industrial units. The Mews that emerged is quirky, open and beautifully landscaped. Existing mature trees anchor the site in time and private gardens are accessed through hidden portals.

As we navigate this current chapter in Planning, with the pendulum swinging from supporting rural barn conversions in favour of urban developments, we need to be wary of being too restricted in our thinking. The arguments which prioritise urban development over rural are sound (e.g.fewer cars driving around the countryside), yet the concern is that rundown rural sites which hold much potential might now be overlooked. Both are golden opportunities for bringing a little joy and beauty back into more densely built environments.